bobs, cages, quivers

Hello all,

I am in Münster, and I want to share some of the particularities of this place, but I don’t know how it all fits together. This month feels different. As you know if you’ve been reading me for a while, spring has always been a hard time of year for me. Maybe the year (unlike projects, books, relationships) is the one thing I don’t know how to begin. Each year I crumble under the pressure to leap out of winter (I like winter!). I want to sprout and blossom, but I am overwhelmed, bogged down by the tribulations of that labor.

I’ve been spending time with a lot of curators. One night, as we made our way to dinner, one of them had the key to the Dominican Church that is the deconsecrated home to Gerhard Richter’s permanent installation of a Foucault pendulum. She offered us an after-hours peek – we stepped into the darkened cavernous space as the curator with the keys ran around switching on the lights.

The Dominican Church was the first of two darkened, ostensibly secular spaces I would visit this month. The second was Münster’s Bible museum, where I spent a morning alone, looking at old books. The museum is one very dark room, up a flight of stairs lined with quotes about and from the Bible. A nice person works in an adjacent office and is happy to help and chat. One cool thing about the museum, for all the book-binding nerds out there, is that it not only chronicles the journey of the bible but also the journey of the book. There is extensive detail about the materials and fabrication process of scrolls, papyrus, paper, bindings, casings, inks, and of course, the world-changing development of the printing press in 1450.

Richter’s Foucault pendulum, like all Foucault pendulums, swings over a magnet, embedded in the center of the dial, which by repelling it keeps it in permanent motion. Due to our latitude, it will take this pendulum in Münster about 30 hours to return to a given point on the dial, which is how Léon Foucault proved the earth’s exact rotation to the Catholic Church in 1851. You can watch this video for more detail about the physics behind this cool and confusing object. Fun fact: Foucault’s original pendulum was re-installed at the Panthéon in 1995, and then at the museum of Arts et Métiers in 2000. In 2010, the cord snapped, damaging the bob (which is the technical name for the heavy round ball of a pendulum) and the marble floors irreparably.

Richter’s pendulum hangs 29 meters long, and the watermelon-sized bob weighs 48. There are mirrors on the sides, so you can see yourself with his work. I wasn’t moved by this artwork when I walked in, but I didn’t know why. Is it uncool, in this corner of the art world, to be enthusiastic about old Gerhard Richter? Everyone’s attitude toward the work carried a drop of derision, and maybe I was influenced by that. The artwork’s slick and modern veneer is the mark of an impermeable aesthetic that leaves me cold. Richter says his work represents a small victory for science, which is weird to me, because that’s what the pendulum is. Does adding mirrors make it an artwork? Their slick surfaces seem to say that they’ve got it all figured out.

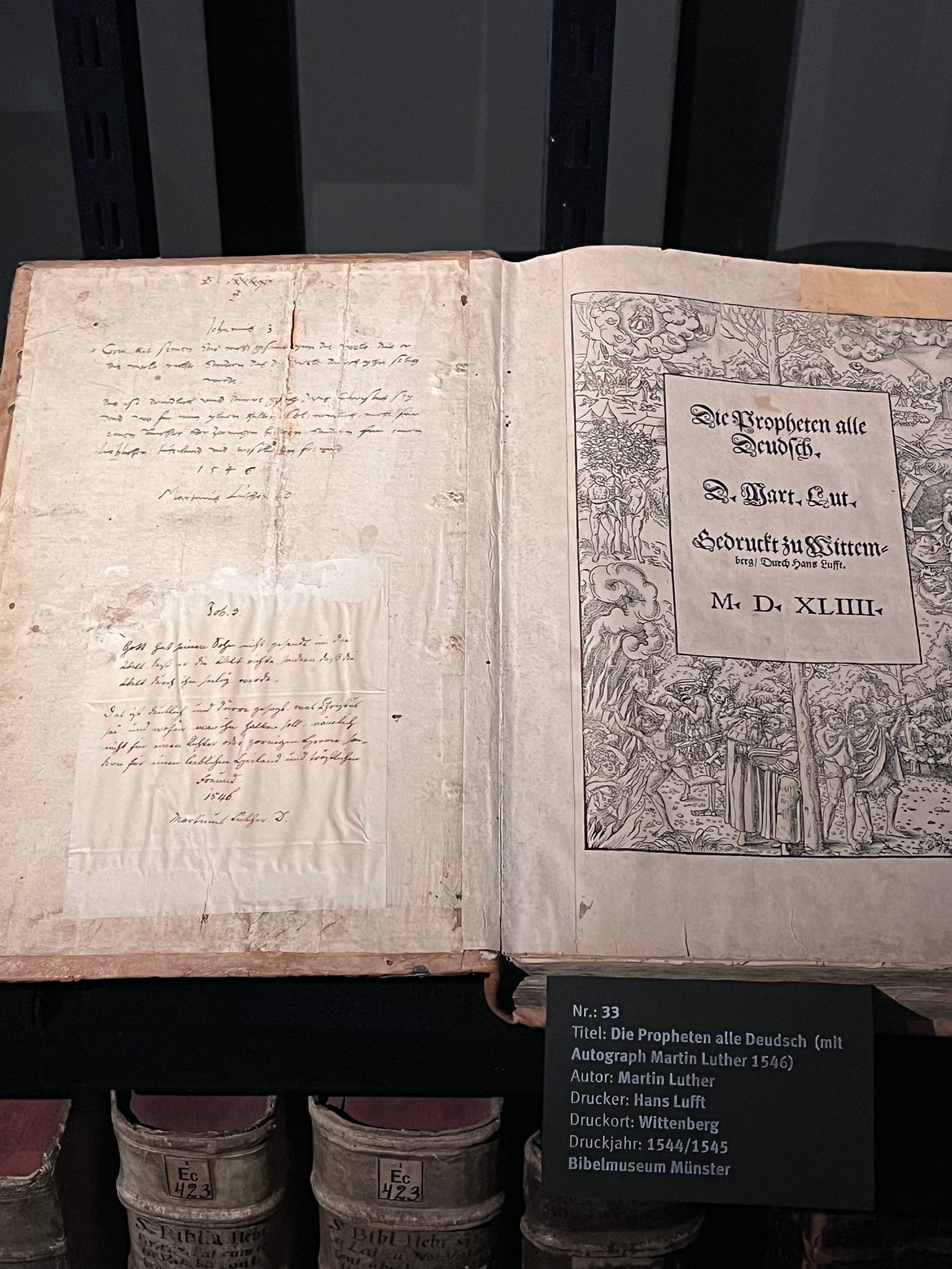

After I had made my rounds at the Bible museum, I asked the office person a well-informed question about the Luther Bible from 1924, something like “hey so this is the one that is a really big deal, right?” He said yes, it is, and added, in his gentle German-inflected English, “but the one next to it is also a really big deal.” He showed me how in this bible, Martin Luther had hand-written a passage from the book of John, and some musings about them.

“John 3

God did not send his Son into the world to save the world, but that the world might be saved through him.

This is clearly and plainly said, what Christ is

and what he is to be regarded for, namely, not as a judge or an angry lord, but as a loving Savior and a comforting friend.”*

My interlocutor said that these lines were probably written in the weeks before he died. They sum up some of his political thinking as well indicate, perhaps, that at the end of his life Luther found some peace with God. When I asked what that meant, he said that Luther famously struggled with his faith, doubt and had a tumultuous relationship to God. I got a little emotional when he said this, probably because I can relate. I like thinking about God as a friend, as a force that is there for me, that is comforting. Through my life there have been moments where that complicity is broken or lost, and honestly, it is a terrible feeling.

When they deconsecrated and renovated the Dominican church, they removed the altar (replacing it with the pendulum), but also the organ, pews, and all religious artwork. They also painted the inside it a dusty pink, which is a decision that I hope at least one person regrets. One alcove, gilded and full of iconography remains, in the back, behind a wrought-iron grate. I guess it was too ornate or expensive to do away with completely. So now it’s there, behind the pendulum, in a weird voyeuristic cage.

As I learned more about the history of the Foucault pendulum, I realized what I disliked about Richter’s. It underlines a triumph won long ago: that of science over religion. His perfect pendulum swings day in and day out, proving something long proven, insisting on a battle already won, which is that science is right. It makes me wonder what else he is trying to prove. When a science/religion dichotomy is set up, or to put it otherwise, when a feel pressure to pick a side and there is only one acceptable side, I basically think it’s annoying and passive aggressive. It’s the kind of artwork that makes people who think they live in a secular society feel above people who they think don’t. No art without vulnerability, right?

There were a lot of other cool bibles-related things at the museum. One was a clay tablet from ancient Sumeria (2nd century BCE) containing an account of creation in which God made heaven and earth, and people from clay, like in the book of Genesis. One was an Ethiopian collection of biblical and liturgical texts accompanied by a travel quiver (made of double parchment, book-binding nerds!). It was open to a beautiful illustration of Saint Gabre Manfras Kiddus letting a thirsty bird drink out of his eye. There was also an ultra-contemporary “Berlin Bible” made by schoolchildren in Berlin, who arranged Legos to depict different scenes, comic-book style.

In this town, one of the most famous churches, St Lamberti, has three cages suspended from the spire, where the corpses of three radical anabaptist who tried to establish a communal sectarian government were left to decompose after the Munster Rebellion in 1534. I don’t have time to get into it but it’s a crazy story. Like, cool ideas but then things got really out of hand – to the tune of mandatory polygamy among other things. These Australian comedians do a good job of telling the story. Martin Luther was actually in favor of stamping down the rebellion and killing all of them. I wonder if that was one of the moments where him and God had beef with each other.

I wandered over the St. Lamberti with Hester one morning to check out the cages, get a pic for the newsletter, and to see if I could feel anything spiritual. Because I was with a dog, I couldn’t go inside. But I tried leaning against the old gal (the church), to sit and journal. It was a nice day out. The cages are the originals. The curator with the keys to the Dominican church said the city changed the way the cages are lit at night. It used to be brighter lighting but now it is more ominous-looking, like orangey fake candlelight. Whatever I was looking for wasn’t there.

Once I visited the church of the Holy Sepulchre, in Jerusalem, and I didn’t feel the tingly presence of the Holy Spirit in there either. It was a shell. No special energy, as if nobody had worshipped there in a while. The same is true for Notre Dame, and definitely true for the Dominican church. Holy places that do house the Holy Spirit or are on an energetic vortex of some kind include, in my un-scientific opinion: the Klosterruine in Berlin, St. Etienne-du-Mont in Paris which is right next to the Panthéon, and James Turrell’s “Meeting” at Moma PS1 in Queens.

Until next time!

Louise

* Johannes 3

Gott hat seinen Sohn nicht gesand ynn die Welt, das er die Welt richte, sondern das die Welt durch yhn selig werde.

Das ist deutlich und dürre gesag, was Christus sey

und wofur man yhnen halten soll, nemlich nicht fur einen Richter oder zornigen Herren, sondern fur einen lieblichen Heiland und trostlichen Freund.