Dear reader of 5, 6, 7, 8,

This month’s edition hosts the Queen of the Heavens and of the Earth, Empress of Despair, and Architect of Your Eternal Suffering, Olympia Bukkakis. If you aren’t familiar with Olympia’s work, I feel sorry for you, but happy to know that by reading further you will become more exposed. What follows is a conversation between Olympia and I, which took the form of an email exchange that I initiated on October 10th and that she ended on November 16th.

If you want to support this newsletter and my ability to publish it for free for everybody, consider upgrading to your subscription, sharing it online, or forwarding it to a friend.

Hi Olympia,

I'm so happy you agreed on this collaboration. You're someone I love to listen to want to focus on. You're a drag queen, a choreographer, a writer, a community organizer, and an activist - you stopped an entire audience from clapping through the curtain call of your show "replay" to lecture them about voting in the Deutsche Wohnen Enteignen referendum. The way you title your drag events, like "Apocalypse Tonight", "Get Fucked", and "Queens Against Borders" betrays a way with words. Your essay "A Case for the Abolition of Men" is currently available through HKW.

You told me you feel "extremely conflicted" about belief. Exciting! Why do you feel that way? The definitions I use to start us off:

Religion is the institution, the one who holds the structure, the "brand" of the set of rites, the dictator of the dogma, the one with the right/wrong way of interpreting the text, the enacter of violence, the house within which communities can commune. Faith is a relationship to unknown, invisible, enormous, and mysterious entities, and it is very personal. Belief is a motion, an inner choreography, a practice of faith, a trick our minds play on us, a way we have been manipulated and oppressed, and one of the most powerful things we do as humans. What do you think of these definitions?

In general, I am devoting this letter to writing about how belief works and what it would mean if we took more responsibility for curating our beliefs. With you, maybe it's interesting to talk about political beliefs. How did you come to believe in the politics that drive so much of your work? Did you shape them or adopt them or grow up with them? How do your beliefs move you? How does it feel to talk about your politics in terms of belief?

Hey hey,

Thank you for your generous introduction! I enjoy this newsletter very much and I'm happy to discuss this enormous topic with you.

My impulse for saying I'm conflicted about belief is that I find myself having the same conversation over and over when people ask if I'm 'spiritual'. I confess that I was *extremely* 'spiritual' as a traumatised and lonely baby queer/trans teenager. My investment in magic at the time came from a desire or need to believe that I had agency over myself, my surroundings, and the wider world. As I grew older I noticed that material actions yielded more reliable results than spells (lol). I realised that despite my need (or desire) to have agency and stability in the world, in a very important sense I don't have those things. This realisation feels sacred.

The spirituality conversation often revolves around acknowledging that there are things in the world that we can't understand. For me that means accepting the void and trying to live with it. For others it means living inside elaborate mythological frameworks, which tend to reproduce neoliberal capitalist (and often homo/transphobic) logics. After I was attacked on the street a few years ago, my friend was talking with a braindead crypto-bigot hippy who suggested that people receive what they send into the world, and then confirmed that this was true in my case. Can you believe that?

But then I fucking love mythology. My drag persona is partly based on Inanna, the Sumerian goddess of love and war, who apparently captained an order of non-binary trans priestexes (love that for her). Storytelling is a way to create and understand the world. Bigotry isn't just a disease of the religious and esoteric.

I can get into Catholicism’s whole camp pagan vibe sometimes, the way I like dipping into tarot and am coming around to astrology. But I see post-Roman gentile Christianity as a coercive and clever way to control a population through the fulfillment of needs, like in an abusive relationship. The confession takes advantage of the human need to share shame, the mass takes advantage of the need to come together. I think the essence (or pre-Christian origins?) of these rituals are beautiful, but then you have an order of sadistic and abusive men taking advantage of that.

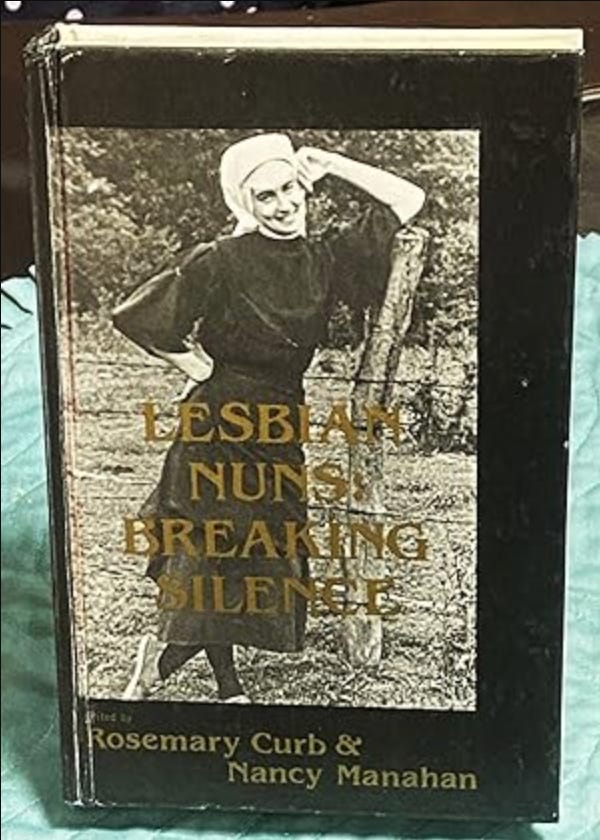

That said, if I was a medieval European woman I'd definitely be lezzing out in a nunnery. Come to think of it, I'd like that option here and now. Alas nunneries give off a bit of a TERFy vibe so I don't think they'd take me.

About my political beliefs: it's interesting to frame it this way. When I was like 5, I remember thinking how strange it was to use money and that we should do away with it. At 36 I'd rephrase it as 'we need to do away with a profit-oriented economy and arrange our societies around human need and cultural flourishing by expanding democracy into the workplace and expropriating the capitalist class (plus or minus a few guillotines)'. And yeah, this is a belief and it requires some kind of faith. It hasn't yet been achieved and it has failed in a number of tragic, informative, or inspiring ways. Rosa Luxemburg has said we're facing a choice of socialism or barbarism and the second option could mean extinction. It's a cold, hard, terrifying fact that the current state of things cannot last forever - let's call that belief under extreme duress.

Olympia! It is so great to read you. Inanna is one of my favorite goddesses and it’s brilliant that she is one of your drag mothers. A summary of her story, as I know it, for the readers: Inanna sat on her throne in a divine kingdom with her husband while her sister ruled the underworld. She decided to visit this sibling and, as she descended, she passed through seven gates. At each gate she had to remove an article of clothing. Upon arrival to this Court of Darkness, the sister suspends her from the ceiling, hanging her from her skin with hooks. Inanna dangles there for three days, until her order of non-binary preistexes free her. When she returns to her throne she has the husband removed and disposed of. The moral of the story? The underworld sister is also Inanna. We learn that in order to meet our shadow-selves we need to be brave, and in order to be brave we need to be vulnerable: disrobed both literally and metaphorically by casting off the filters and veils that occlude our senses.

I love the way you expressed the void, the not-knowing. For me, esoteric practices have led me to question and complexify my faith. I’ve learned to make meaning, to trust my interpretation and know it is an interpretation, and to develop secure attachment with the great mysteries of the universe. You asked if I can believe that a self-proclaimed spiritual person told you that you got assaulted because of how you send out energy. Yes, I can believe that, and I am sorry that happened. I don’t believe energy is ours, sendable, or otherwise controllable. A relationship with spirit, like any relationship, is a practice, not a dogma or logic.

Let’s talk about political beliefs. Right now in Germany and elsewhere we are witnessing a gross mishandling of shame, as well as the results of unexamined beliefs about what life means and whose lives matter, and also whose deaths matter. We are implicated in a contemporary holy war, which might shed light on holy wars past, by which I mean that the extent to which they are about the unfathomable love of God is laughable (cry-able). The Holy Wars around the 11th century, which sought to debilitate early Islamic expansion, were more about controlling power, land, resources, than they were about spreading the good word (although one begets the other). This one is no different.

It makes me think about an operating mechanism of belief that I am chewing on - tell me what you think about it. Humans do and think violent things “in the name of”, and when the violence of the doing and the thinking is “in the name of”, somehow it no longer counts as violence and gets transformed into righteousness, which affirms the name, protects the people who claim the name. Any threat to the people then becomes a threat to the name, which legitimizes more violence. And the name itself is never clear. In whose name? God’s? The state’s? In the name of the living? In the name of the dead? Do any of these names, or the many behind the one name, actually want this violence? I wish more people were brave the way Inanna is brave.

Ok I could talk about Inanna with you for days. I haven't heard the interpretation that her sister, Ereshkigal (a wonderful name for a girl in case anyone's expecting), was her shadow self. I really like it! I read a theory that this story is actually a hymn to Ereshkigal, rather than Inanna. Another tidbit is that Inanna is described as wearing mascara called 'let a man come'. Go off babe.

This mishandling of German shame is such an upsetting thing about living here. I first found out about the mind-blowingly ignorant and selfish worldview of the so-called 'antideutsche' when a leftist jewish Australian friend came to visit and she kept getting these weird lectures from Germans about what her position on Palestine/Israel should be. (I have a secret theory that these Germans are in fact deeply in love with Germany, they are in fact secretly proud that they are the *best* at being bad, with the exception that muslims are worse). The thing is that many Germans are actually nowhere near ashamed enough. Shame should hold white gentile Germans back from harassing this friend or calling Judith Butler an antisemite, but for too many it doesn't. The Jewish Antifa Berlin once posted ( I'm paraphrasing): 'Jews, Israelis, Arabs, and Palestinians are more than just spectres that haunt the German imagination, they are flesh and blood people'. Seeing gentile Germans instrumentalise history and guilt in a way that causes harm to real people in the present is maddening to me. I think all Christian Europeans and their descendents in the colonies have a special responsibility to interrogate their own inherited prejudices and hatreds.

It's worth considering the process of appropriation and abstraction that involved the Jesus movement turning from an insurrectionary movement for Jewish self-rule and independence from the Romans into a gentile death-cult fully endorsed by the empire. What antisemitic biases were baked into Christianity from the start? I think we would be better off looking into this than projecting our millenia-long crimes onto migrants and muslims.

Statistics show that the vast majority of antisemitic hate crimes in Germany are committed by white gentile Germans. If the German state was serious about tackling this, we would be hearing about massive restructuring and restaffing (denazification) of the police, army, and intelligence forces, huge investments in public education (including history) in areas where antisemitism and racism are on the rise (everywhere btw), and a raft of policies that improve the lives of the poor and working class so we don't have so many people wondering why their living standard has dropped so precipitously (reason is billionaires btw). Instead we have cops stamping out funeral candles for dead Palestinian children on Sonnenallee.

I (don't) hate to be so predictable but this 'in the name of' touches on a central problem in revolutionary socialism. The bolsheviks were working in desperate circumstances with innumerable enemies, and the Leninist approach was 'the ends justify the means' or 'if you want to make an omelette you gotta break some legs'. Rosa Luxemburg (and I'm assuming all of the anarchists) had problems with this. But then she (and they) were killed. I have to confess I'm agnostic on this. I'm definitely not a non-violent resistance zealot here. The existing violence of capitalist exploitation, neocolonialist extraction, and the literal destruction of a habitable earth necessitates a compromise on the purity of tactics for sure. But I guess every situation demands a specific response. Strict nonviolence, holy rights to land, and God-given missions to civilise the world are all strict dogmas that function to blind us to the peculiarities of the situation in front of us. Every person deserves a home, a vote, the means to sustain themself and the people they love. How we get there is undoubtedly a fucking mess though.

My mind landed on your words “Shame should hold them back.” One of the first times I discussed the harmful aspects of being raised Christian with my father, I asked him about how he lives with the guilt intrinsic to Protestant culture. He said he likes it, needs it, that it helps him, and that it holds him back from doing things that are bad. That’s not how I experience it, and I believe it works for him that way.

A psychologist might say that at the root of guilt and shame is fear, and fear is there to signal potential danger. Olympia, you used shame in the positive sense, as in, shame is supposed to curtail bad behavior. I believe that too. I disagree with the idea that Germans aren’t ashamed enough. If shame wasn’t an overblown, terrifying, constant pressure of a mode of oppression – a famous operating mechanism of belief – maybe it would function properly. Christian European culture instrumentalizes guilt and shame in order to propagate itself and its supremacy. The ways in which Christian values, whether catholic (I am bound to my leaky, messy, sinful body that hurtles towards death) or protestant (I must work harder, I work alone), provide the scaffolding for capitalism and machinery for white supremacy are many. But then we’re left with no one to take responsibility for German cops bludgeoning kids in my neighborhood. I mean, ACAB, but this is bigger than the individual cop. Oder?

I am intrigued by what you said about early Christian history, how it began with emancipatory air under its wings and then an anti-semitic bias was baked into its inception. By “process of appropriation and abstraction,” are you talking about a scenario in which early Christians, in order to gain legitimacy and power, had to distance themselves from Jews, while keeping the parts of Judaism that suited them? If so, I love that analysis, and want to think more about ways of telling Christianity’s origin story. If not, can you explain again?

Okay last thought – down with purity and zealots of all kinds! Thank you for explaining your thoughts on the messiness of the revolution. It’s a scary thing to say you’re not 100% non-violent all the time. I’ve never considered the upsides of having access to and knowing how to safely operate a firearm more than after reading Octavia Butler’s Parable series. Scary!

I think you're onto something with the surplus of Christian shame creating a situation where it's difficult for us to know when we actually should feel it (in order for it to be a socially productive force) and when it's just some old guy in bad drag telling us not to have anal. So I do agree with you there. And funnily enough I initially struggled with ACAB because I thought the whole point of the structure of the police force is that it doesn't matter whether every cop is a bastard or not, because at pivotal moments the structure will force all cops to behave like bastards even if that goes against their instincts. Then I realised that bending to that pressure is precisely what being a bastard is. So ACAB!

I'm not a bible or religious history scholar (lol), but from what I understand there was an early schism after the death of Jesus between the Jerusalem church, led by David, Jesus' brother (look it up he actually existed!) and Saul (Paul), who never actually met Jesus except for when he got high or something on the road to Damascus and hallucinated him. Our Christianity comes from the guy who hallucinated Jesus (which is a vibe). The disagreement may have been around whether followers of the Jesus movement had to follow Jewish laws (including circumcision). The Jerusalem church (led by Jesus’s brother) said yes. Paul's camp said no. Which was… convenient for starting a movement in an empire where the majority of people were not, in fact, Jewish. Again I'm not an expert but what I know makes me suspicious.

There were heaps of different sects and cults following Jesus in the centuries after his death, some of which are truly coconuts. This means that there were lots of options for what kind of Christianity would ultimately triumph (he pops up in Islam too) and there are historical and political reasons why the present one did, and how, and this raises questions about what the effects of those reasons are today. Two millennia of antisemitic violence and repression indicate that there may, in fact, be something very questionable about the version we have, and we would be much better off focusing on that, rather than projecting our guilt onto migrants'

Regarding (non)violent resistance, I'm reading a book that unpacks the communist manifesto called “A Spectre, Haunting” by China Mieville. It discusses the different times Marx and Engels thought violence would and wouldn't be necessary. There's to this day a big schism on the left (the actual one, not the one including the traitorous dogs of the former social democratic parties) about how and when aggressive tactics would be necessary. I'm more convinced by the argument that it's always necessary to build a mass movement and a pretty broad social consensus so that any violence (inevitably started by the cops or other repressive state forces) can be overcome quickly and as peacefully as possible. But given that we all experience capitalist repression all the time, I'm not going to pretend the problem starts when someone throws a molotov cocktail, you know?

Thank you Fjola Gautadotir for your eyes on this text. The edited version of 5, 6, 7, 8 was approved by Olympia. Olympia, thank you so much for speaking with me this way - please enjoy a virtual round of applause from Ryan Gosling and the readers for your words, work, time, and lifelong political practice.

If you, dear reader, enjoyed this, consider sharing it with a friend, posting a screenshot on social media, or becoming a paid subscriber.

Below are some resources for ways you can take steps to move you and those around you, beyond participating in social media, away from the effects of prolapsed shame, the genocide in Palestine, and the perpetuation of a climate of violence that affects us all.

Berlin:

Resources gathered by COVEN BERLIN, as read in “A Thing That Feels”

Kampagne für Opfer rassistischer Polizeigewalt supports victims of police violence at demonstrations

Rote Lilly for legal support

As deportations pick up, let’s support: https://www.instagram.com/abolishdeportationprison.ber/

Berlin Against Pinkwashing: https://www.instagram.com/berlinagainstpinkwashing/

Resources gathered by the group Sickness Affinity Group in EN

DE:

https://pad.riseup.net/p/r.b3f8fea48469026a71c204a3889eea83

These two articles are particularly helpful for getting a sense of how this is playing out in Germany

Jewish Currents: an examination of the pitfalls of 'Memory Culture' in Germany (EN/DE)

Jewish Currents: An Anti-Palestinian Crackdown Across Europe (EN)

Also via COVEN An entire library of books on Palestine and Israel, digitally accessible from @junny.girl (EN)

Sign the petition to save an helpful functional community center in Berlin, Oyoun, whose funding got cut after a Jewish Voice for Peace organized an event.

Manufacturing Consent in Germany is a collection of freely accessible materials that provide a structural understanding of the increasingly repressive climate within Germany. Central to this is the nationalized politics of Holocaust remembrance, which has been effectively instrumentalized, as is clear from the various articles, lectures, press releases, and podcasts, by the right-wing in Germany.

And here is a collection of free pdfs about liberation, the left, anarchism, and spirituality, from @anarchospirituality.

Podcasts:

Hamas/ with Tareq Baconi on “The Dig” for some thorough historical context.

Loneliness of the Israeli Left by Jewish Currents’ podcast “On the Nose”

USA, Canada, and UK-focused resources can be found here, replete with guides for calling or emailing your representatives, donating, and finding demos.

As we know, half the population in Gaza is children. The Palestinian Children’s Relief Fund has been providing free medical care there for 30 years, and since the war in 2014 it organized orphan sponsorships for nearly 300 kids. Because the situation in Gaza has, to use the PCRF’s words, “spiraled into one beyond a scope any of us could have imagined,” like most aid organizations and initiatives, they have needed to pause their efforts. Donating now will help ensure that when they regain contact with their surviving staff in Gaza and are allowed back in, they will be well-equipped to get to work.