Stories in Ruins: Part II

Nuremberg, of all places

Disclaimer: in this edition of 5, 6, 7, 8, I will be taking liberties in speaking about history. I am in no way a researcher, historian, or expert. My sources are Wikipedia, an interview with Thomas Zeitler, the minister of St Egidien’s Kulturkirche in Nuremberg, and a handful of other conversations. Read this as you would a horoscope.

A few weeks ago I performed in Lester St. Louis’ piece “In Residence.” It was supposed to happen in some cool warehous-ey space that ended up getting shut down, forcing us to move to St. Egidien Kulturkirche. Erected in 1150, this former benedictine monastery sits on a hill on the north side of Nuremberg’s Altstadt.

I gathered that Nuremberg’s story is bracketed by two moments in history caught in an eternal face off, creating a disoriented mise en abîme effect.

In the late middle ages (1300-1500), Nuremberg was one of the biggest towns in Europe. Due to its central location at a trade route crossroads, as well as a thriving metalwork industry, the town was mega wealthy. Add the money coming from Germany’s first colonial endeavors (a guy of the Tetzel family, entombed at St. Egidien, ran a copper mine in Cuba, for example) and you get massive, gothic, whose-church-is-bigger architectural pissing contests: Frauenkirche, St. Lorenz, St. Sebald, and, to a lesser extent, St. Egidien.

The Renaissance is famous for its sexy Italian vibe à la hyperrealistic oil paintings, perspective, and greco-roman architectural drag. The German “flavor” of Renaissance is more practical and prescient – the printing press and Protestant Reformation, of which Franconia and Bavaria was the center.

The Reformation was a movement beyond religious doctrine, whose ideas became core tenets of our contemporary lifetime. You would recognize them: individualism, privacy, the word is God, and money is secular. The ‘protestant work ethic’ so instrumental to capitalism sings that same song: I do my work, I own my property, it is between me and myself to make heaven on earth. None of the confessional, showy, perform-it-to-the-whole-village Catholic fanfare. Social responsibility was taken away from the church’s alms system and put into the hands of secular authorities. It’s stripped down, somber, and hinges on the merit of the ONE rather than the tides of the many.

Nobles and intellectuals in Nuremberg were partial to the independent thinking and individuation that it fostered, and wanted to be ‘freed from the shackles’ of the Catholic church. They were in the throes of wealth generation and world-imagination directly linked to colonial endeavors that were bringing in stories, lands, foods, and other extracted riches. These stories from abroad allowed the nobles to make ruins of the Catholic narrative. It’s a pattern. When a group takes stories and uses them to get power, to get free, to break shackles they feel to be under, it is at the expense of another group and their freedom, agency, power. While this pattern of making ruins of one another is a tale as old as time, this instance of it was built to last: if it’s printed, it’s God.

After the Reformation and until the late 19th century, time stood still in Nuremberg. Its growth slowed and stuttered to a stop. They rested on their laurels and big churches, as the rest of Germany and Europe grew. The world behind Nuremberg’s medieval walls became a bubble, frozen in time. The Romantics rediscovered it at some point and thought omg this place is super cute and medieval! How quaint! And then Hitler arrived and thought, ah, yes, this is the story I need: this is what Germany really is.

The Nazis expressed themselves through architecture, both by identifying with an architecture of the past (enter Nuremberg) and by building one for the future: grand avenues, a colosseum, huge stadiums for the massive Reichsparteitage, all of which Hitler desperately hoped would materialize his fascist worldview. The Leni Reifenstahl footage of the Wehrmacht parading down big streets, or the crowds hailing, were shot in Nuremberg. It was the scenography or backdrop of Hitler’s fantasy land and the decor of that narrative.

There is a term I learned that came out of Nuremberg. It is “Butzenscheiben Romantik.” We’ll need a picture to explain it.

Given the crafty energy of Nuremberg in the middle ages, and the beer industry it is known for, many windows in Nuremberg were built out of the rounded glass of the bottom of a bottle. Being concave, the glass distorts what’s on the other side. So although it is possible to see through these windows, one’s vision is occluded. The term is connected to Nazi times, for they thought that they were seeing a real Germany, when actually they were just being Butzensheiben Romantikers, projecting whatever story could stabilize their ideology, saying, look, it’s plain as day!

So these are two important moments for Nuremberg: the late middle ages and the Nazi era. The second relies on occluded vision, turning back and projecting something onto the first, making sure that only one version of the story could be seen through the window. The first is known as a golden age, but whose gold and whose expansion is the protagonist, and whose names never get written down?

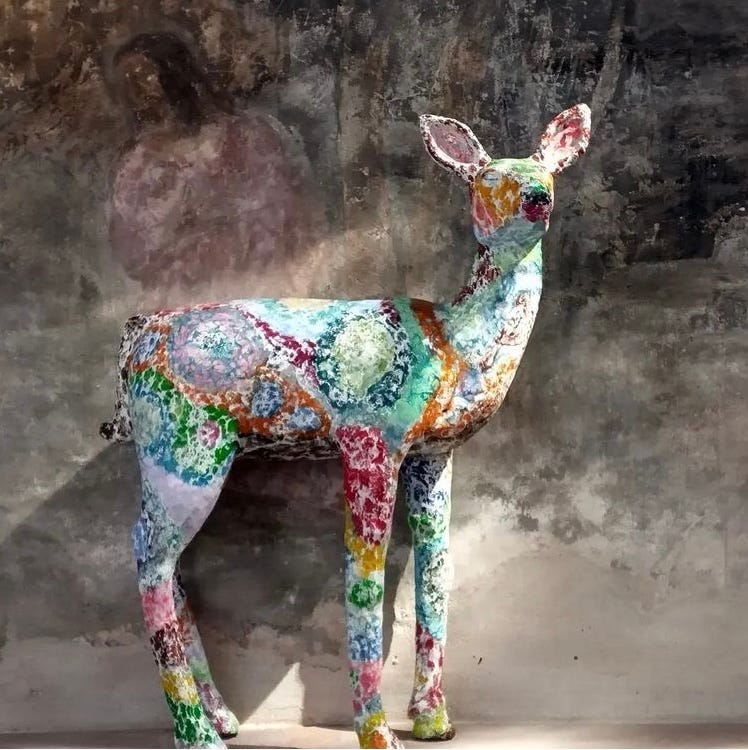

Part of my job as an invited artist in Lester’s work was to hang out with audience members and have conversations. My station for these chats was in the back chapel, dated from 1350 or so and originally built by nobles to honor their ancestors, attached to the rest of St. Egidien later on. I was tucked into a corner, underneath a colorful statue of a doe.

Many visitors interrupted our chats to exclaim, “ooh I don’t know if I can say this in a church but…” and it made me love how this church contains so many more stories than it did before, and so many kinds of stories. I’ve visited a lot of churches in my life, as well as other holy sites (like some hammams, some theaters, graveyards, the wailing wall.) The places where people pray collect the energetic residue of their worship, I feel, and when you visit a holy site you feel the texture of all that residue, and each place feels a little different.

I like to imagine that the conversations we had at St. Egidien, by virtue of being in a church that is almost one thousand years old, were a form of worship. If they are, then how did our worship change that space? What residue did we leave? What was it we were worshiping?

Many audience members being from Nuremberg, we talked through relationships folks had with this town as well as random shit people had on their minds. Like, if big cities were lovers, what kind of lovers would they be and what would they ask of you?

Paris: is mean, makes you beg, loves you when you leave but ignores you when you return

Munich: pretentious, a liar

New York: much to give, can be anything you want, but you’ll need to work hard to keep up the affair and next thing you know you’re stuck

Berlin: easy and cheap good times, love-able, leave-able, lose-yourself-able

Nuremberg: marriage material

(this was made in collaboration with a visitor, Eric, who lives in Nuremberg)

Thomas, the minister, told me his version of the story of the patron saint Egidius, and it really touched me, so I wanted to share it with you as a parting note.

English speakers might better recognize St. Egidius as St. Giles, his anglo name. Basically, young Giles was from a noble Greek family in the 6th century, and his parents died tragically when he was young. So he became a hermit in a forest in the lower regions of the Rhône, and was visited every day by a doe, who gave him her milk and helped him survive. One day, King Wamba, an “anachronistic visigoth” came a-hunting the doe, but Giles shielded her with his body and got shot in the arm. King Wamba was so taken by Giles’ humility, because I guess St Giles ended up converting this powerful pagan, that he built him a monastery.

Thomas is socially active in many political ways, notably when it comes to environmentalism. His spin on St. Giles is that his relationship with the doe is shamanic, in the sense that their lives are bonded thanks to their mutual sacrifice and generosity with one another. They both gave of their bodies for the well being of the other. Thomas likes to use it as a metaphor for the relationship between humans and the earth, saying “I live as long as you live and if you die, so do I.”

This edition was guest edited by Thomas Zeitler, notably for some semblance of historical accuracy, as well as by OG Nurembergian Jonas Schuh.

The work “In Residence” was initiated by musician and installation artist Lester St Louis, curated as part of the Musik Installationen festival. The other performers in the project were amazing, and I warmly invite you to check them out. They are: Vanessa Sin, artist and DJ from Lausanne; Chris Williams, trumpeter and installation-maker from New York; Nikima Jagudajev, old friend, choreographer, and writer; and Emeka Okereke border-breaking artist and video maker.

Lil’ Announcements

~ This weekend I am doing a one-on-one performance that I developed in collaboration with Nikima, called CRITS. It will be held at Fortuna Wetten on Friday 12th and Saturday 13th within the frame of T.E.N.T’s Lotto Royale! You must register in order to attend - all info and registration here.

~ Happy to announce that I was awarded Take Heart research funding to keep doing what I’m doing, which is research the intersection of faith and dance. I’ll be headed to the US in a couple days for some focused writing time as well as an interview with Katy Pyle, the founder of Ballez.

~ My current dramaturgical job working The Superimposition, by Melanie Jame Wolf and Martin Hansen, is well on its way! I cannot wait for you all to come see the public presentation of this research at Bärenzwinger on September 18th.

~ My most recent article has just been published in SPREAD, about the first ever edition of the Club for Performance Art Gallery. It’s called “Excavating the Forever Interred” because it is also about Pompeii. You can read it here.