Four years ago I started to read The Artist’s Way, which led to writing morning pages, which turned into an idea for a book. The book is about dance and God, or at least that’s what I say when I don’t know how much attention my interlocutor has for me. My thesis statement has gone through many formulations, the earliest of which was that dance is an interesting case study for how we understand the operating mechanisms of belief, like devotion, ritual, and indoctrination. But really, what I want is to share my experience of God and through doing so I want to address a crisis of meaninglessness and belonging, because dance and God have so much in common, and talking about dance is less alienating.

One of the challenges of this project has been defining my terms. In a recent newsletter with Olympia Bukakkis, I defined religion, faith, and belief like this:

Religion is the institution, the one who holds the structure, the "brand" of the set of rites, the dictator of the dogma, the one with the right/wrong way of interpreting the text, the enactor of violence, the house within which communities can commune. Faith is a relationship to unknown, invisible, enormous, and mysterious entities, and it is very personal. Belief is a motion, an inner choreography, a practice of faith, a trick our minds play on us, a way we have been manipulated and oppressed, and one of the most powerful things we do as humans.

But how to define God? A “peace which passes all understanding” is attributed to God in a prayer that I tattooed on my right thigh, facing me so that I can read it every time I go to the bathroom. It has been important through the writing process to situate my relationship to God within my religious tradition, knowing full well that God slips through the cracks of definition. I wanted to situate God this way because of the urgency of writing politically about belief, about the structures humans come up with to get in touch with God, like rituals, as well as the institutions humans make to guard their God. These are deconstructible and relatable things that we have some or no control over.

It is really hard to talk about God without talking about violence. How can I reconcile this with how what I feel from and for God is love, all the time. How to describe this love, in my book? And is this love a form of violence? Is it a blind spot? I find myself avoiding it, deleting passages that sound too cringe or too privileged, reverting instead to more familiar modes of critique, attempts to signal my awareness, and funny anecdotes.

There was the year I was 15 and I moved away from my childhood home, and stopped going to church, choir, youth group, and acolytes. I was in a place that I thought would be welcoming and familiar, but it wasn’t. There wasn’t room for how lost and sad I felt. This was the year I started smoking cigarettes. There was this wall you could sit on that was invisible to the street, in the parking lot of a church in the small town I lived in. I walked there to smoke in secret. It was fall and there were all these wet leaves on the ground, and I don’t know what I was thinking but I looked down and the yellow of some of the leaves jumped up in response to whatever was in my head, in a way that was so clearly God. This wordless communication was the ultimate recognition of myself in the world, saying everything that was not me was also a part of me.

It’s beautiful to say that God is everywhere and God is love and there is God in each one of us. I believe those things. But it’s interesting to say, as Mayra Rivera says, that God is wholly other, yet of us, and that we know otherness intimately through knowing the divine. Transcendence is this realization that you store everything that is not you within you, so while you are intricately connected to the world, you are also always an alien to yourself.

In my daily life, God helps me empathize with things that seem foreign or unfamiliar to me. God helps me push the limits of my own mind and body, not in the sense of being sinless or more productive, but more as embracing the constant push and pull of absorbing information in the world, and making meaning with what I absorb. God is there in the absorption, in the sense that God helps me to be open to things that I cannot imagine; God helps me learn and listen. God is also there in the meaning-making, in the sense that I want to live my life trying be an artist the way God is an artist. The phrase ‘God is love’ only makes sense if God is why I try to take care and take responsibility for what I create. The times when taking care and taking responsibility do not happen are, like, very very frequent. That’s when another important push-pull comes in: it’s okay, keep trying.

If this sounds like big statements, that’s because it is. It’s everything and everywhere all the time. It’s an impossible chaos. I don’t know how to talk about it on smaller scales.

Things get violent when we expect God to provide certainty and predictability, cause-consequence, or belonging — when we expect God to make relating to anything outside of ourselves make sense or feel safe. God doesn’t work that way. God, as we know from quotidian horrors, like when your doctor doesn’t believe you, to global horrors, like all the wounds in Gaza right now, passes all understanding. God is both the gift that you have access to a doctor and fact that the healthcare system is broken. In a place like Gaza right now, God shows up both as pain and as resilience. God cannot be good or bad or blamed or savior, yet God is both the best and worst and also something else, more complex and chaotic.

Chaos again, I know. I think this is where the rituals, rites and religions come in. Easier to talk about, to feel a sense of control, to have an opinion about and to critique and espouse. These things are ours to make meaning with and take responsibility for. I can’t talk about all of them because I don’t know enough, but I can talk about dance.

How to define dance? Somehow that’s an even harder task. Maybe dance is how being a body is being a vessel, a channel, a container, a meaning-maker, a participant in the push and pull, a thing that suffers and loves and lives and dies, that includes so much more than what any one person (our most flawed unit of measure!) can contain. Maybe to be a dancer is to practice being in balance, in graceful relation to the paradoxes that be.

Love,

Louise

PS: after four years of writing about belief and what it means to believe, I almost always spell the words wrong, like this: beleif, beleive. Does anyone know if this is a word in another language? Any etymologists with some insight about this omen-as-spelling mistake?

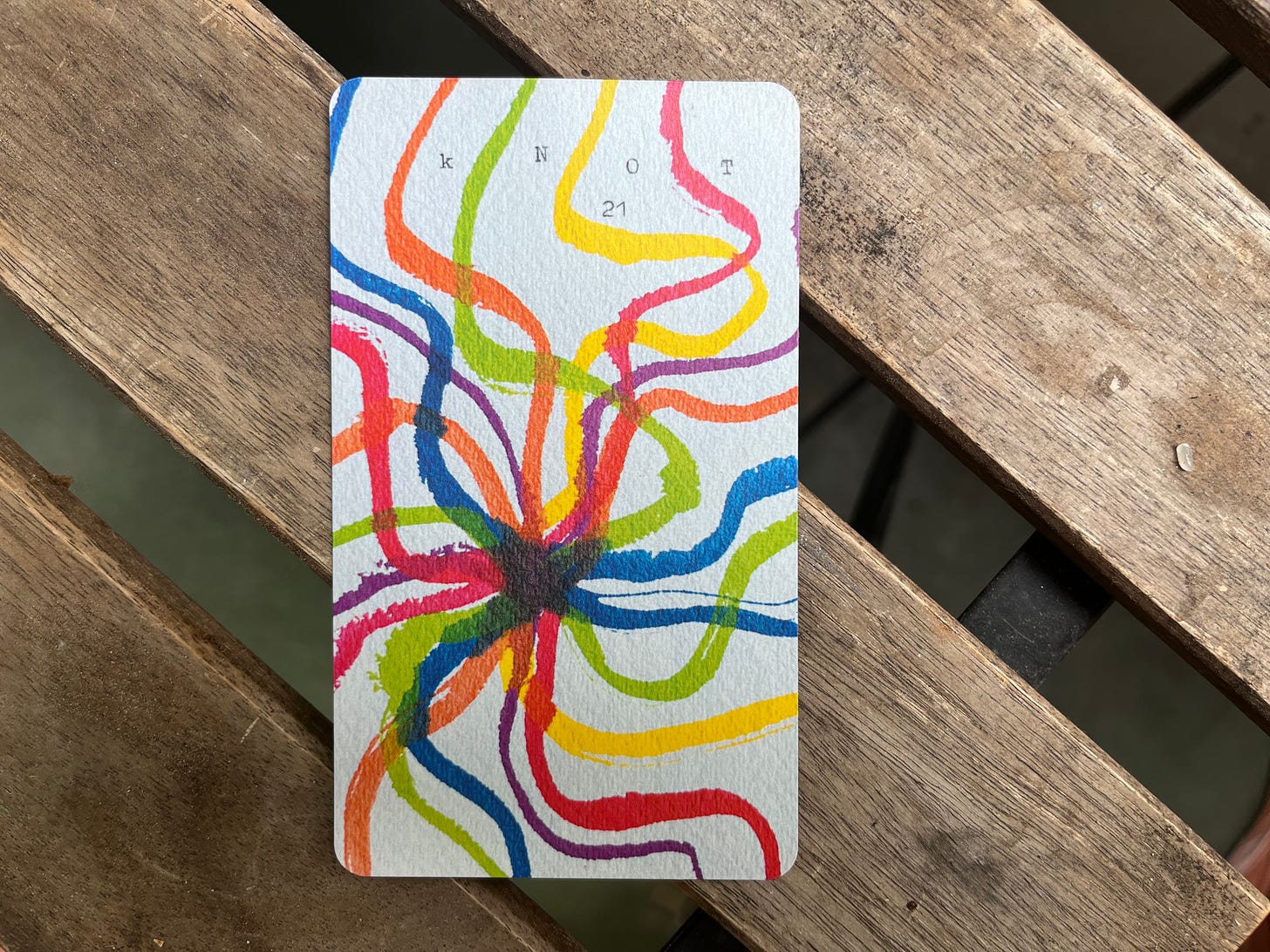

PPS: the title of this month’s 5, 6, 7, 8 comes from a card I pulled in a deck created by Maria Francesca Scaroni and Ezra Green. It’s called “knot” and here is part of the description:

How many things are true at once? Maybe all of them. At the center of the Knot is paradox, indelible ambiguity, fundamental and never undone. And yet, and yet.

This card is work, a patient and impatient untangling that wants liberation. This card is also rest, a gentle or rough acceptance of the abiding tenacity of the knot.

~ If you want to support this newsletter and my ability to publish it for free for everybody, consider upgrading to your subscription, sharing it online, or forwarding it to a friend. ~

Very honest and beautiful writing....